How far we have strayed from this great wisdom!!

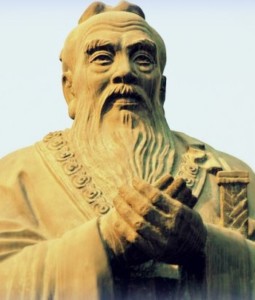

Confucius (551 BC–479 BC) had as central to his philosophy the concept of Deliberate Tradition that would organize society around education, the content of that education, and the social life that would engender.

Confucius used five key terms to describe how this would be implemented: Jen, the virtue of benevolence and love; Chun tzu, the ideal person, who as the opposite of the petty, mean, or small-spirited person, was real and authentic, someone at home in the universe; Li, a kind of savoir faire, the knowledge of how to comport oneself with grace and urbanity whatever the circumstance—in those key relationships between husband and wife, elder siblings and junior siblings, ruler and subject. The fourth key term is Te, which means power, specifically the power by which people are ruled.

Confucius wanted to address the fallacy of oppressive rule. He rejected the Realists’ claim that the only effective rule is by physical might. He showed how past Realist dynasties (Ch’in, for example) had been stunningly successful at the start, but collapsed in less than a generation. Confucius noted that the three essentials of government were economic sufficiency, military sufficiency, and the confidence of its people. He stressed that the popular trust was by far the most important, for “if the people have no confidence in their government, it cannot stand.”

This spontaneous consent from its citizens, this morale without which nations cannot survive, arises only when people sense their leaders to be people of capacity, sincerely devoted to the common good and possessed of the kind of character that compels respect. In the final analysis, goodness becomes embodied in society neither through might nor through law, but through the impress of persons we admire.

If the leader whose sanction springs from inherent righteousness, such a person will gather a cabinet of “unpurchaseable allies.” Their complete devotion to the public welfare will quicken in turn the public conscience of local leaders and seep down from there to inspire citizens at large. For the process to work, however, rulers must have no personal ambitions, which accounts for the Confucian saying, “Only those are worthy to govern who would rather be excused.”

The final key to Confucius’ society was Wen. This refers to “the arts of peace” in contrast to “the arts of war.” It refers directly to music, art, poetry, and the sum of culture in its aesthetic and spiritual mode. He also added a political dimension to this notion of wen, and how it succeeds in international relations. Here again the Realists answered in terms of physical might; it was the answer Stalin echoed in the last century when, asked how the Pope figured in a move he was contemplating against Poland, asked in return, “How many battalions does he have?”

Ultimately, Confucius maintained that victory goes to the state that develops the highest, the most exalted culture—the state that has the finest art, the noblest philosophy, the grandest poetry, and gives evidence of realizing that “it is the moral character of a neighborhood that constitutes its excellence.” In the end, it is these things that elicit the spontaneous admiration of women and men everywhere, and thus establish a deliberate tradition of civilization.

His views on statecraft still have important messages for us today.