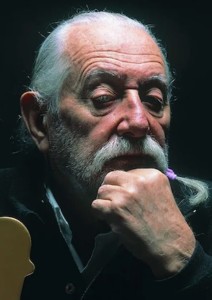

Ettore Sottsass, Italian Architect, Designer, and Founder of the Memphis Group, (1917-2007), from a video from 2000:

I find it very difficult to talk about contemporaneity. The fate of contemporaneity does not stop anyone, but I cannot—with the tiny cells of my brain—adhere completely. I have a vision of it that is not as happy, optimistic, or as hopeful as the industry and tech propaganda want to assert it as being. I have a basic intention, which is to preach calmness. One of the things that scares me the most is this culture of competition. We talk about success, selling, not selling… (as though) life is an act of competition. I wonder where this begins and where it ends.

Can we preach a culture where relationships are always carefully studied and, if anything, dulled, rather than accelerated and sharpened? In contemporary industry, there is a large distribution of competitive culture—through advertising. For example, the impact of multinational corporations is the result of competitive aggression against underdeveloped countries. We’re making agreements to rip them off. These aspects of contemporary culture don’t calm people, but make them nervous. There is a great state of general neurosis—and a designer, at this point, what can he do? Increase these general neuroses, or try to create objects that calm people.

I hate the word ‘creativity’, because it is a word invented on Madison Avenue by advertisers. It’s clear that the industry needs to renew itself continuously, because otherwise it does not sell. People get bored, generations change and you have to change everything. This is about industry, it’s not about society. Industry needs advertising, and advertising needs creativity because the market needs to renew itself continuously. It’s a game; it’s a destiny. Since there has been industry, it has gradually been subjected to its own destiny—which is what it is.

I don’t think that Leonardo considered himself a creative person, and I don’t even think he considered himself an artist. He considered himself a technician who was capable of doing these things—capable of making a horse so powerful to please his Lord, or the warrior placed on it, and to express this situation. I believe that all antiquity was made more by craftsmen than by artists. Much less talk about creativity or foolishness or surprises.

It may be that contemporary society, precisely because of these mechanisms of accelerated communication, is accelerating on all sides towards a consumption of existence that is conditioned by the necessity of industry, and may continually need spectacle, and therefore creativity. Everything must be spectacular. Fashion is always new. Cars are always new, even medicines are always new. The way of walking is always new. The ways of going on vacation. The ways to know the world—everything is accelerated and always new.

It may well be that a humanity will be born for which life, existence, is permanently a spectacle. I do not know this, and I don’t criticize it either. I know that creativity—that is, invention—is strictly conditioned from market needs. And the needs of the market are strictly conditioned by the production itself. It’s a closed circle. So, I would like to end here. I’ve thrown a stone in the pond, let’s see what happens.

There is much to think about in this view. The pressure to be contemporary and to leapfrog beyond what exists, in some ways, is fear-based. We don’t like to face liminal space, or the in-between experience of resting and rejuvenating and ripening to new expression. On the other hand, the universe is naturally expanding and we are naturally evolving, so allowing our creativity to align with that natural urge, to contain universal principles and truth, is part of our joy. We must check ourselves concerning our motivations. And we must look to creating long-lasting, more universally applicable designs, systems, and products.